In the years since free speech and academic freedom experts Erwin Chemerinsky and Howard Gillman published their book Free Speech on Campus, which explained the importance of free speech at colleges and universities, much has changed as colleges faced new pressures and tests and sought to adapt to the changing political climate.

Institutions created—and later abolished—diversity initiatives in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Campuses weathered the brutal COVID-19 pandemic. State legislatures increased their meddling in what public university faculty can and cannot teach.

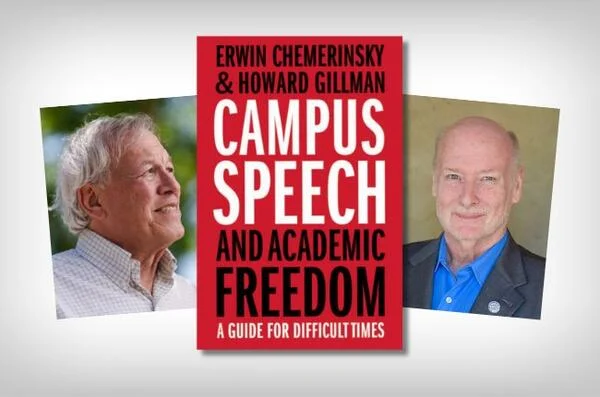

Chemerinsky and Gillman’s second book, aptly named Campus Speech and Academic Freedom (Yale University Press, 2026), addresses complicated questions that aren’t necessarily answered by basic speech principles. For example, what obligation do universities have to cover security fees for controversial speakers? Or, does an institution have a responsibility to protect employees and students who are doxed for online speech?

The book was initially scheduled to publish in 2023 but was pushed back and will be released this month.

“Our editor at Yale Press told us he was never so pleased to have a manuscript come in late,” said Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California, Berkeley—2024 ended up being a year ripe with speech-controversy examples that ultimately strengthened the book, including college responses to the Oct. 7 attack; congressional testimonies from the presidents of Columbia University, Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California, Los Angeles, about campus antisemitism; and student and faculty encampments in protest against Israel’s actions in Gaza.

Chemerinsky and Gillman, chancellor of the University of California, Irvine, co-chair the University of California’s National Center on Free Speech and Civic Engagement. They are both well versed in First Amendment law as well as campus leadership. Inside Higher Ed spoke with Chemerinsky and Gillman over Zoom about the modern challenges that university leaders face in responding to speech and academic freedom controversies on campus.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: It’s been about nine years since the two of you last wrote a book on this topic. What do you hope this book adds to the conversation about campus free speech?

Gillman: At the time we wrote the original book, there were very basic issues about why you should defend the expression of all ideas on a campus that were not resolved. If you remember in 2015–16, there were strong efforts to demand that universities control speakers or prevent certain people from speaking. And at the time, a lot of university leaders … didn’t have the language to explain why a university should tolerate speech that a lot of people thought could be dangerous or harmful.

So we thought we needed to cover the basics. But once you accept that it is a good idea to protect the expression of all ideas, it turns out there’s lots of questions. What do you do about regulating tumultuous protests or people who think that they’re entitled to disrupt speakers with whom they disagree? What do you do about security costs if the need to protect the speaker puts enormous pressures on the budgets of universities? What do you do about speech in professional settings, which maybe shouldn’t be governed by general free speech principles? … So we knew we needed to reassert the importance of the basic principles of free expression, but then we had to systematically go through and address all of the issues that aren’t resolved by that basic question, and that’s what we hope the new book does.

Q: And I have questions about those new questions you answer in the book. One is about institutional neutrality. For a university that claims to have core values like diversity and social justice, couldn’t silence on major global events be interpreted as a violation of those values?

Gillman: We note that a lot of universities have embraced the Kalven report, which suggests that universities should very rarely speak out on matters that are of political debate, because universities should be housing critics and debate rather than taking strong stands. We review how many state legislatures were demanding that universities embrace a policy of neutrality when it comes to political statements.

But the view that we have is that neutrality is really not possible because, as you say, universities are value-laden institutions. It is inevitable that universities are going to take positions. We note, for example, in the wake of Oct. 7, some university leaders took a position and said things that led to controversy. Some university leaders initially attempted not to say anything, and that led to controversy. So we suggest that neutrality is essentially impossible, but university leaders should show restraint for all the familiar reasons—that you need to allow for enough debate on the campus. It’s more important for campus communities to have their voice, rather than for universities and their leaders to always jump in.

Chemerinsky: We both reject the Kalven report approach of silence for university leaders. I think that it’s a question of, when is it appropriate [to speak]? This is an example where, like so many in the book, we never imagined we’d be writing from a first-person perspective, but a lot of the book ended up being written that way. For me, it’s always a question of “Will my silence be taken as a message, and the wrong message?” As an example, I felt it important to put a statement out to my community after the death of George Floyd, and I thought it important to make a statement to the community after Jan. 6. So I very much agree with what Howard said about the importance of restraint, but I also reject across-the-board silence.

Q: Something else you address is how professors approach certain academic materials in the classroom. We’ve seen professors in hot water for reading certain historical texts or using slurs for an academic purpose. Where do you draw the line between the professor’s right to determine their curriculum and the university’s responsibility to prevent a hostile learning environment for students?

Gillman: Professors in professional settings do have the academic freedom as well-trained, ethical professionals to speak in ways that are consistent with their professional responsibilities. So the classroom, for example, is not a general free speech zone where professors can walk in and say whatever they want. We try to provide lots of examples of case studies where professors said and did some things that some people in the classroom or the larger academic community would have objected to, but nevertheless reflect legitimate judgments of how best to approach the issue.

It is inevitable that if you give professors freedom of mind, that some of them are going to exercise their professional competency in ways that some people disagree with. So we try to suggest lots of examples where that academic freedom should be protected, but we also try to identify some examples where people were acting in ways that were not consistent with either their academic competence or their professional obligations. Once you understand the basic boundaries and responsibilities of faculty—not just their privileges, but their responsibilities to act in professional ways—we think that’ll help people do a proper assessment and not always just react whenever what a professor says in a classroom is causing some controversy.

Chemerinsky: I obviously agree. I think your question also raises another major issue that occurred between Free Speech on Campus and this book, and that’s the tension between free speech and academic freedom and Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Former assistant secretary for civil rights Catherine Lhamon was very outspoken in saying, “Just because it’s speech protected by the First Amendment doesn’t excuse a university from its Title VI obligations.”

It’s certainly possible that a professor in class could say things that are deeply offensive to students, and [the students] could say, well, this is creating a hostile environment under Title VI. Then the issue becomes: What should the university’s response be? As Howard said, you start with assessing academic freedom—is it in the scope of professionally acceptable norms? To take a recent example, a professor who would go into a computer science class and use it to discuss his views on Israel and the Middle East, that wouldn’t be protected by academic freedom because it’s not about his teaching his class.

Q: Another scenario for you: Event cancellations related to security concerns for speakers feel especially relevant after Charlie Kirk was killed during a campus event. But not all institutions can necessarily afford security for high-profile controversial speakers. For those institutions, would a budgetary-based cancellation be distinct from a speech-based cancellation, or are they the same?

Chemerinsky: The answer is, we don’t know at this point in time. In fall of 2017, a conservative group on the Berkeley campus had scheduled a free speech week, and they invited Milo Yiannopoulos, Ben Shapiro, Ann Coulter and Charles Murray. It cost the university $4 million in security to allow those events to go forward. But what if it wasn’t free speech week? What if it was free speech semester? And what if the cost was $40 million? There has to be some point at which a university says we can’t afford it.

Gillman: But there are certain principles that should govern how you think it through. You need general rules that you apply to every circumstance, but those rules cannot, in effect, be discriminating against people based on their viewpoints. So if your rule is “well, any time a controversial speaker is proposed, we’re worried that it’s going to cost too much in security, so you’re not allowed to bring controversial speakers,” that will create viewpoint discrimination on campuses. It would mean, for example, on a liberal campus, that every liberal student group would always be able to bring their speakers in, but conservative student groups could not.

Q: Right, because what’s controversial would be subjective.

Gillman: Very subjective. So you need a rule in advance … We review in the book a few choices. At the University of California, Irvine, we charge people exactly the same security cost based on the same criteria—the size of the group, how big an event it is, whether you need a parking facility and the like. If we think that there is going to be external [controversy], or other concerns that are not under the control of the sponsoring student group, then the university has to cover those additional costs. Now, so far, that hasn’t bankrupted my university. But, by contrast, UCLA realized that it may quickly end up blowing through its budget, and so they created a policy that, in advance of the year, limited the total number of dollars that they were going to use to cover security on events. Once they blew through that budget for the year, they weren’t going to allow other kinds of speakers after that. You need rules that you will apply in a viewpoint-neutral way and that do protect the expression of all ideas. But then those rules have to be mindful.

Q: One more for you: There were debates, especially in the 2023–24 academic year, over campus encampments and what constitutes a disruption of the educational mission. If a protest on campus is peaceful, but it occupies a space for weeks, is it the duration of the protest or the existence of it that justifies its removal?

Chemerinsky: Campuses can have time, place and manner restrictions with regard to speech, and the rules are clear that they have to be content-neutral. So a campus can have a rule saying “no demonstrations near classroom buildings while classes are in session,” or “no sound amplification equipment on campus,” or they can restrict speech near dormitories at nighttime. As part of time, place and manner restrictions, a campus can say that they’re not going to allow encampments for any purpose, whatever the viewpoint, whatever the topic.

It then becomes a question of, should the campus choose to have such a rule? And how should the campus decide about enforcing that rule? One of the parts of the book that I’m most pleased with is where we go through and offer suggestions to campus administrators about things to consider when dealing with encampments. How much is the encampment disrupting the actual activities? How much is there a threat of violence? How have similar things been dealt with before? What kind of precedent do you want to set? What action might you take, and what would be the reaction to it?

Gillman: I think that very few people believe that individuals or groups of people on the campus or off the campus have a right to come and commandeer a space on the campus for themselves and to do that for an extended period of time. A campus may decide it doesn’t want to rule against that, but I think everybody would understand if campuses had rules against encampment activity. But it has to be viewpoint- and content-neutral.