Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board is expected to deny an application for a Jewish charter school Monday, but will likely welcome organizers of the school to take them to court.

Peter Deutsch, founder of the Ben Gamla Jewish Charter School Foundation, and a former Democratic congressman, made his pitch for the school in January, saying that he aims to bring “a rigorous, values-driven education” to Jewish parents in Oklahoma.

“I anticipate that our board would like to grant them the application,” Brian Shellem, the board chair, told The 74. “But we can’t snub our nose at the court either.”

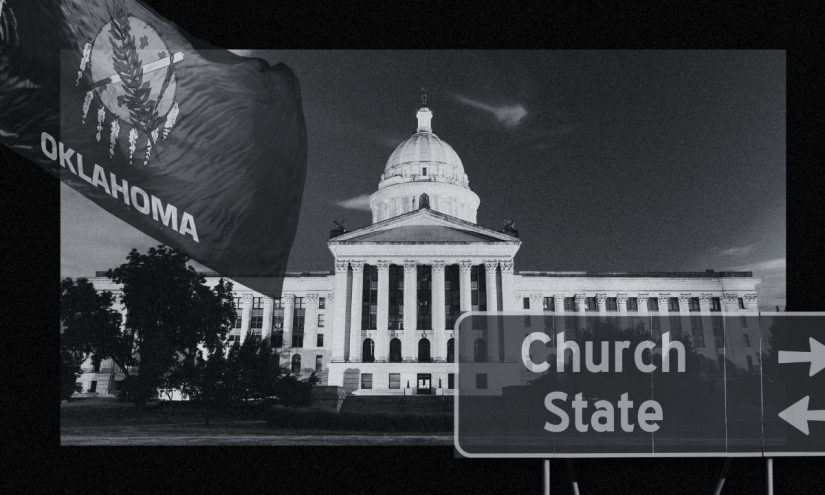

He means the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which ruled against the nation’s first Catholic charter school in 2024. That decision still stands after the U.S. Supreme Court deadlocked over that case last year. The charter board’s likely denial of Ben Gamla’s application is expected to spark another lawsuit, pitting supporters of religious charter schools against those who say it would violate the Constitution’s prohibition on establishing a religion. With a case over a proposed Christian charter in Tennessee already in federal court and another religious school in Colorado founded to test the same legal question, there’s little doubt that the nation’s highest court will eventually settle the debate.

After 4-4 Supreme Court Case, More States Jump on Religious Charter Bandwagon

“It is hard for me to imagine the court doesn’t take the issue again when it comes to it,” said Derek Black, a constitutional law professor at the University of South Carolina. But after Justice Amy Coney Barrett recused herself in the case over St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, resulting in the 4-4 tie, the justices likely in favor of religious charters, he said, “would want a case that was very strong.”

Mysterious Recusal Could Upend Pivotal Supreme Court Charter School Case

‘Pray and hear Scripture’

So far, the only case to watch is in Tennessee. Wilberforce Academy of Knoxville, a nonprofit that wants to open a K-8 Christian charter school, sued the Knox County school board because the district wouldn’t accept its letter of intent to apply. State law prohibits charter schools from being religious.

“Students will begin to develop biblical literacy in kindergarten and begin taking catechism lessons by third grade,” according to Wilberforce Academy’s request for a quick ruling in the case. “And they will pray and hear Scripture together in a school assembly every morning.”

As St. Isidore did before them, Wilberforce argues that the nonprofit is a “private actor” and that approving its charter application would not turn it into a government entity.

The Knox County board told the court that it will “most likely” not take a position on the legality of Wilberforce’s argument. On Thursday, the board will hear a resolution asking state education Commissioner Lizzette Reynolds to consider granting Wilberforce Academy a waiver so they can open the Christian school.

The Knox board, however, also said the issue of religious charter schools “deserves a thorough examination by the federal courts.”

Judge Charles Atchley Jr, for the Eastern District of Tennessee, thinks so, too. Last week, he allowed a group of Knox County parents and religious leaders, who oppose Wilberforce’s application, to intervene.

The case, he wrote, has the “potential to reshape First Amendment jurisprudence in the educational context” and it wouldn’t serve the court or parties involved to not have “vigorous advocacy on both sides.”

Amanda Collins, a retired Knox County school psychologist, is among those who have signed up to fight against Wilberforce Academy. She has two children still in the district and one who graduated in 2024. She grew concerned about Wilberforce Academy when she learned the organization didn’t have a history of operating charter schools in the state and feels its attorneys are using the district to “merely force an issue up the ladder to the Supreme Court.”

“In Tennessee, we have plenty of things that are underfunded,” she said. “We don’t need to be wasting our local Knox County taxpayer money on somebody’s agenda that is not intended to promote the education safety and wellness of our public school students.”

‘The clear constitutional boundary’

Another school that could spark a lawsuit over public funds for religious schools is Colorado’s Riverstone Academy, which advertises that it offers students a “Christian foundation.”

The school operates “pretty much just like a charter school” said Ken Witt, executive director of Education reEnvisioned, the board of cooperative educational services, or BOCES, that contracted with the school.

As Chalkbeat reported, emails between the attorney for the Pueblo County district, which allowed the school to open within its boundaries, and the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative law firm, suggest the school was intentionally founded to test the legal argument over whether public schools can practice religion.

After threatening to withhold state funds because of the school’s religious mission, the Colorado Department of Education funded Riverstone’s 31 students. But the state is also conducting a thorough audit, which could take another year, before deciding whether it can legally provide money to the school. In the meantime, Riverstone had to close its building last week because of health and safety violations. It’s unclear whether students are learning remotely or in another facility in the meantime.

For now, Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser, a Democrat running for governor, hasn’t issued an opinion on Riverstone, but his views on St. Isidore, the Oklahoma school, were clear. Last year, he led 15 attorneys general in opposing state funding for the school.

In a statement, he urged the Supreme Court “to preserve the clear constitutional boundary that protects both religious liberty and the integrity of our public education system.”

Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, a Republican who is also running for governor, made a similar argument about St. Isidore before both the Oklahoma and U.S. supreme courts.

But that’s where both he and Weiser split with the Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti. In his opinion, Skrmetti states that categorically excluding faith-based schools from public charter programs violates parents’ rights to freely exercise their religion.

To Ilya Shapiro, director of constitutional studies at the conservative Manhattan Institute, it’s a matter of equity. Higher-income families can move into wealthier neighborhoods or pay private school tuition, he wrote in a recent commentary on the Wilberforce case. The state, he added, already funds religious schools through education savings accounts.

“But families who rely on charter schools are told that their options must be secular,” he wrote.

Black, with the University of South Carolina, said the issue comes down to who authorized the school to begin with. In both Oklahoma and Tennessee, either local or state boards approve charter applications.

“That explicit state involvement, to me, makes it clear that state action is involved,” he said, “and thus the Establishment Clause applies.”

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how