Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Each February, National Career and Technical Education Month spotlights the growing reality of Americans rethinking the connection between education and work. The old education-to-opportunity pipeline is increasingly under strain.

Employers struggle to find skilled workers. Families increasingly question the cost and payoff of a traditional college education. And young people are entering a labor market reshaped by artificial intelligence and rising credential requirements. Entry-level jobs that once served as stepping stones now demand prior experience, and skills grow obsolete faster than ever.

For much of the past half-century, education policy rested on a simple promise: Prepare students for college, and opportunity will follow. That formula has weakened. College completion remains uneven, student debt burdens are widespread and too many graduates leave school without clear routes into stable, well-paying work.

Research reinforces this unease. The Lumina Foundation reports that the economic payoff of postsecondary education varies widely by school, degree level and field. As a result, the central question families ask is no longer “College or not?” but “Which pathway pays off — and when?”

Career and technical education has much to contribute to this conversation. No longer a specialized option or a consolation prize, CTE has become central to preparing young people for work, adulthood and economic mobility.

It also reflects a broader shift in how Americans think about success, away from a single, linear path toward opportunity pluralism — the idea that there are multiple legitimate routes to a good life, and that education systems should support many ways forward.

What Makes Some CTE Programs Great While Others Fall Short?

In fact, enrollment in CTE programs — which The National Center for Education Statistics defines as high school classes and post-secondary career-focused courses that lead to credentials other than a four-year degree — is rising steadily. Education Week’s Research Center reports that K-12 CTE participation rose roughly 10% between the 2022-23 and 2023-24 school years, reflecting expanded offerings and rising student demand.

And the shift toward career-focused post-secondary education is even more pronounced, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

More students are signing up for undergraduate certificates and associate degrees than for bachelor’s degrees, with enrollment growing by 1.9% and 2.2%, respectively, compared with 0.9% for bachelor’s programs. Community colleges now have approximately 752,000 students in undergraduate certificate programs, a 28.3% increase since fall 2021.

Public opinion has also shifted. Surveys show a growing willingness among parents and the general public for CTE and other forms of technical and trade education for high school graduates. Families and students are voting with their feet, applying a return-on-investment lens to decisions about education and work.

Today’s CTE looks very different from the vocational education of the past. Historically, vocational tracks typically functioned as sorting mechanisms, steering low-income students and students of color away from academic options into job pathways with limited mobility. A 1992 study of high school vocational education characterized it as “low esteem, little clout.”

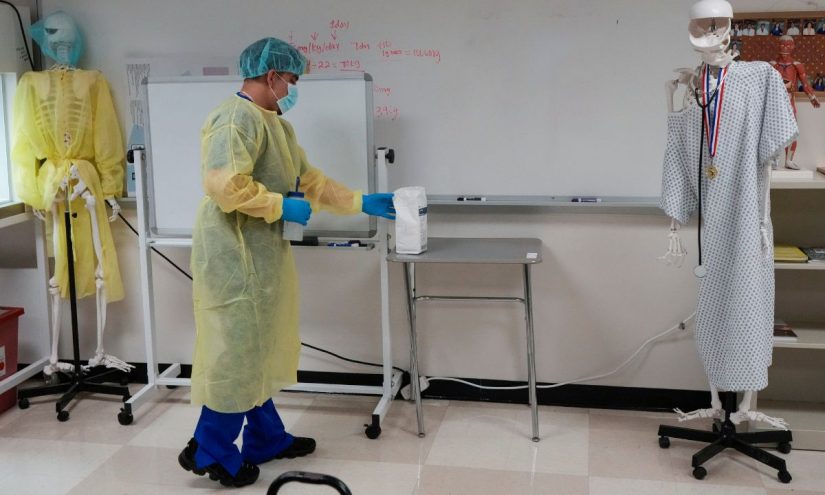

Modern CTE breaks from that legacy. It emphasizes career pathways that integrate academic learning, technical skills, work-based experience and postsecondary education. The goal is not to force students to choose between college and career, but to blend the two to preserve choice and enhance advancement.

Evidence supports this shift. EdResearch for Action finds that the strongest CTE pathways align academic content with occupational skill development rather than treating the two as competing priorities. When done well, integration raises, not lowers, academic expectations.

This approach aligns closely with opportunity pluralism. Rather than treating a four-year degree as the sole marker of success, it acknowledges that people acquire knowledge, skills, identities and economic stability in different ways. It treats work as a legitimate place for learning, not a fallback for those who in the past would have been declared “not college material.”

New Report Reveals the Struggle Worldwide to Prepare Young People for Work

CTE today is best understood not as an alternative to college but as a system that connects secondary education to credentials, degrees and careers. Roughly 85% of public and private high school graduates complete at least one CTE course, reflecting how mainstream this approach has become.

But as participation expands, quality becomes the defining issue. An Advance CTE 50-state survey concludes, “too many states lack robust systems, policies and data to ensure true quality and value.”

Research identifies several design principles that distinguish strong CTE programs from weak ones.

Labor-market alignment. Strong programs begin with real demand in regional economies and adapt as industries evolve, rather than relying on static course catalogs. This is important for continuous improvement.

Academic and technical integration. Students shouldn’t have to choose between mastering algebra and learning advanced manufacturing, health sciences or cybersecurity. Effective programs show how academic knowledge functions in the workplace.

Work-based learning is core infrastructure. Internships, apprenticeships and paid work experiences are not add-ons. They help students understand professional norms and expand social capital by connecting them to adults who translate effort into opportunity.

Ladders, not dead ends. Course credit should be portable and transfer across education and training organizations and employers. Credentials should build on one another so that learners are on career pathways to better jobs. The goal is sustained mobility through multiple on-ramps that keep individuals moving through an opportunity-pluralist system.

Credential Chaos: Career Certificates Boom in High School, But Not All Have Value

Persistent gaps remain. There is insufficient funding, outdated equipment, limited space and little evidence of effectiveness. There is an acute shortage of qualified instructors, especially in fast-moving fields. But opportunity pluralism depends not only on offering multiple pathways, but on ensuring they are credible and worth pursuing.

Career and technical education matters more than ever. Whether it fulfills its promise depends on what happens next. Here are four suggestions.

- Treat CTE as core infrastructure. Align K-12, postsecondary and workforce systems so students experience a coherent continuum rather than a maze.

- Match investment to demand. Facilities, equipment and instructor compensation must reflect CTE’s central role in economic mobility.

- Make quality and evidence central. Track outcomes, set standards and improve — or end — weak programs.

- Embrace opportunity pluralism. Value multiple pathways to jobs in addition to college and design systems that allow movement between education and work without penalty.

CTE matters more than ever because the old promises about education and work are no longer sufficient. National CTE Month is a reminder that the challenge is not whether CTE will grow, but whether it will grow well, connecting learning to opportunity at scale.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how