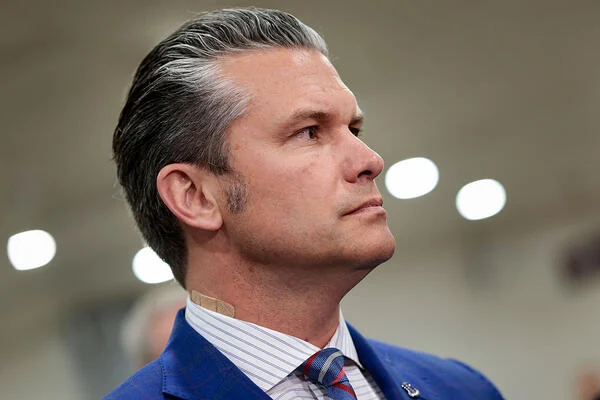

Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth announced this month that the Department of Defense will no longer send active-duty military for graduate-level professional military education at Harvard University. In a video announcing the decision on social media, he claimed that officers returned from Harvard with “heads full of globalist and radical ideologies.” He added, “We train warriors. Not wokesters.”

Before I begin, I will lay my cards on the table. I am a medically retired Air Force major from a traditional, conservative, Southern Baptist background in east Tennessee. At Harvard Kennedy School, I was elected executive vice president of the student government, which represents more than 1,000 graduate students. I say this not to posture, but because I believe this decision warrants a response from someone who was in those classrooms, not as an observer, but as a leader in the student body.

Politics aside, severing ties between the military and Harvard is a mistake. While at HKS, I had the opportunity to participate in most student organizations, meet with both student and administrator leadership, and drive many of the social and policy discussions (formal and informal) across the school. In each of these settings, military members were active participants: injecting keen insight, stimulating robust dialogue or voicing perspectives that no one else in the classroom had considered.

What troubles me most about Hegseth’s announcement is that he offered neither data, evidence nor metrics to support the claim that Harvard-educated officers graduate less capable. While invoking General Washington’s assumption of command of the Continental Army in Harvard Square or the number of Harvard-trained Medal of Honor recipients, Hegseth played to emotional appeal rather than demonstrable metrics or data that support his action. But gambling with our nation’s top officers’ professional education from a well-established world-class institution is a high-risk, low-reward proposition.

In July 2025, the Kennedy School launched the American Service Fellowship, the largest single-year scholarship in the school’s history, for at least 50 fully funded scholarships worth $100,000 to American public servants, with about half of awardees expected to come from military service. Dean Jeremy Weinstein said in the press release announcing the fellowship, “There’s nothing more patriotic than public service.”

Over the past decade, HKS has trained numerous active-duty, veteran and reserve members. The list of prominent leaders with military ties includes Hegseth himself, former defense secretary Mark Esper, Senator Jack Reed and U.S. representatives Dan Crenshaw and Seth Moulton. If Harvard truly “loathes” the military, then why is the institution investing millions to bring more service members to campus?

In justifying the decision, Hegseth also asserts that Harvard has partnered with the Chinese Communist Party in its research programs. A June 2025 investigation in The Wall Street Journal reported that a 2014 Shanghai Observer article referred to HKS as the CCP’s top “overseas party school,” as decades of Chinese officials have pursued executive training and postgraduate study at HKS. But rather than supporting Hegseth’s case, this fact undermines it. If China’s future leaders and officials are vying for access to Harvard’s faculty and resources, why would we voluntarily surrender our domestic infrastructure for future officer development? The proper response to a competitor’s investment in an institution is not to abandon it, but to double down instead.

Consider what we are depriving our nation’s top military leaders of benefiting from. Harvard ranks among the top universities in national and global rankings, and Harvard’s Office of Technology Development reports approximately 391 new innovations, 159 U.S. patents issued and $53.7 million in commercialization revenue in fiscal year 2025 alone. As a prior procurement-contracting officer, these are big-deal numbers. They represent cutting-edge research and development that can rapidly accelerate our defense capabilities and technologies. I remain skeptical about an unfounded decision to deprive our top future military leaders of access to that caliber of institutional infrastructure and the opportunity to build interpersonal relationships with HKS’s scholars, policymakers and faculty.

Personally, given my preconditions—moderate conservative, white male with a Southern Baptist upbringing, east Tennessee native and ex-military—I did not face discrimination at Harvard. In fact, I was elected to the second-highest student position at HKS. I did not encounter wokeism outright (it almost seems archaic at this point). I can say I was not brainwashed or forced into indoctrination camps for expressing differing viewpoints whether in class or on paper. I found that I am not alone in this thought, either.

Former Indiana governor Eric Holcomb, a Republican, published an op-ed in The Washington Post titled “I was a red state governor. What I saw at Harvard surprised me.” The governor writes that he was warned by friends about “woke lions” but found open-minded, problem-solving–oriented students from all 50 states. Former Arkansas governor Asa Hutchinson, also a Republican, served as an Institute of Politics resident fellow at Harvard in fall 2024, when he led small student groups on bridging America’s political divide, which I attended. During my tenure at HKS, the Harvard Republican Club hosted Steve Bannon, Peter Thiel and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and the Institute of Politics hosted Kellyanne Conway and Kevin McCarthy. In short, I find it difficult to characterize Harvard as an echo chamber.

When I think back to my tenure, I remember the many meetings with the dean of HKS and administrators. I remember a seasoned scholar almost obsessively driven to find common ground through constructive dialogue. I remember the vision committees navigating changes in policy, governance, technology and AI. The top student affairs administrators I met with on a weekly basis were genuine and empathetic individuals who wanted the best for student outcomes regardless of differing political or religious ideologies. I witnessed deep learning occurring with many service members, both senior and junior officers, in my classes and heard their sentiments of appreciation for their educational experience at Harvard.

Harvard makes an easy target, but a focus on easy targets makes for bad policy. This decision does not protect our military; instead, it reduces its capabilities. It deprives our best officers of access to the kind of rigorous, diverse, uncomfortable and intellectual environment that produces top strategic-level thinkers, not worse-off ones. Pulling our officers out of these environments does the very opposite of training resilient warfighters: It perpetuates a homogeneous environment and denies our future leaders exposure to world leaders. If we truly believe that we must cultivate the best minds and capabilities of the warrior class, then we should trust our officers, invest the resources and meet the challenge, not run from it.

Allan Cameron is a medically retired Air Force major who served as the executive vice president at the Harvard Kennedy School Student Government. He is an Air Force Academy graduate and holds an M.P.A. from HKS and an M.B.A. from the Naval Postgraduate School. He is currently a student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.