There are the conventional steps educators in the District of Columbia have taken to boost students’ math achievement — increasing rigor, providing extra supports and undertaking deep data analysis.

And then there are the outside-the-box methods.

Math field trips. Collaborations among public, charter and private schools. Unapologetic funding increases. Quick pivots when interventions don’t work.

“We’ve just seen this steady drumbeat of progress,” says Paul Kihn, deputy mayor for education in the District of Columbia. “It really is a story of investment” into high-quality instruction and the expansion of public charter schools that has “allowed all kinds of interesting innovations and collaborations.”

Different metrics show overall improvements in the city’s K-12 math performance in recent years. On the math portion of the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress, 67% of the city’s 4th graders scored at basic, proficient or advanced levels. That’s up from 57% in 2022 and 36% in 2003.

The city’s 2024 NAEP math score for 4th graders was just 3 points lower than the national average and 3 points higher than average scores for public schools in large U.S. cities.

On the 2025 citywide math assessment, 31.2% of students in grades 3-5 met or exceeded expectations, up from 28.4% the previous year. Of the students in grades 6-8: 26.4% met or exceeded expectations, up from 22.4% the prior year. And 15% of students in grades 9-12 met or exceeded expectations, which was an increase from 11.4% the prior year.

DC posts steady math increases on NAEP

The city’s 4th graders outperformed students in 11 other large districts on the 2024 National Assessment of Education Progress.

Kihn attributes the gains to several factors, including increased per-pupil funding that helped boost overall teacher salaries to an average $110,000, instructional improvements like acquiring high-quality classroom materials, and enhanced professional development.

“None of this stuff happens in a vacuum,” he says. “It’s not like we waved a magic math wand and said, ‘This is all going to be better.'”

These instructional improvements and teacher investments have been in place for two decades, Kihn says.

Another factor in raising math achievement rates — a $20 million public-private partnership called the Capital Math Collective led by the DC Public Education Fund, which aims to make Washington the first urban school district where every student outperforms the national average in math by 2030.

A bulletin board — in a staircase at Center City Public Charter Schools’ Congress Heights campus in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 22, 2026 — encourages students to think of math solutions as they move between classes.

Kara Arundel/K-12 Dive

While Kihn and others involved in the efforts celebrate the progress, they acknowledge that a lot of work remains to see more math gains across all student groups.

For instance, the 2024 NAEP citywide results showed economically disadvantaged students’ average score was 45 points lower compared to other students. Black students’ average score fell 65 points lower than that for White students — a gap that was not significantly different from that in 2003.

One of the toughest barriers to this work, Kihn says, is erasing negative math mindsets. He says it saddens him when he hears a student say that they are not good at math or are resigned to not understanding math.

“Part of our work here is the mindset work to help everyone — teachers, parents and most importantly, students — understand that we are all math people,” Kihn says.

Niya White, center, principal of the Congress Heights campus of Center City Public Charter Schools, greets students as they arrive for school on Jan. 22, 2026, in Washington, D.C.

Kara Arundel/K-12 Dive

‘Lots of hard work’

At the Congress Heights campus of Center City Public Charter Schools, a strong belief that all students are capable of high math achievement has helped propel achievement, says Principal Niya White.

On the 2025 statewide math assessment, 70% of the school’s 8th graders met or exceeded expectations. That compares to 25% of 8th graders citywide and 64% of 8th graders in Ward 3, the city’s most affluent area. Congress Heights is in Ward 8, the city’s lowest-income area, where only 15% of 8th graders met or exceeded expectations on the math assessment.

When White became principal of the school in 2012, there had been five other leaders in the previous five years. At the time, the school, which now has 300 students from age 3 pre-K to 8th grade, had low teacher retention rates, disappointing test scores and high discipline rates.

The work of turning around the school and increasing academic proficiency has been slow and steady, White says.

It has included offering summer school and Saturday tutoring sessions, taking students on math-themed field trips, offering pre-Algebra in 7th grade and Algebra in 8th, infusing professional development into the school calendar, and forming public-private partnerships focused on math improvements, including teacher development initiatives in collaboration with traditional public and private schools.

The work also includes being very transparent with families about their child’s strengths and needs, and being ready to support students’ efforts at improvement. One such support involves giving students math manipulatives — physical objects like blocks, dice and clock faces — for practicing math concepts at home.

Part of our work here is the mindset work to help everyone — teachers, parents and most importantly, students — understand that we are all math people.

Paul Kihn

Deputy mayor for education in the District of Columbia

Additionally, the Congress Heights school provides planning time for teachers to prepare for co-instruction so they can help students who need extra support.

“There’s no magic formula,” White says. “There is lots of hard work. The hard work has to be done with consistency and with a team that can handle it.”

It also required creating a school community belief that Congress Heights students can perform at high levels, says White, who grew up attending public and private schools in D.C.

“There were a lot of assumptions made on the students in this building, by way of, essentially, where they come from, who they are and what they look like. And we didn’t buy into and subscribe to a lot of that,” she says.

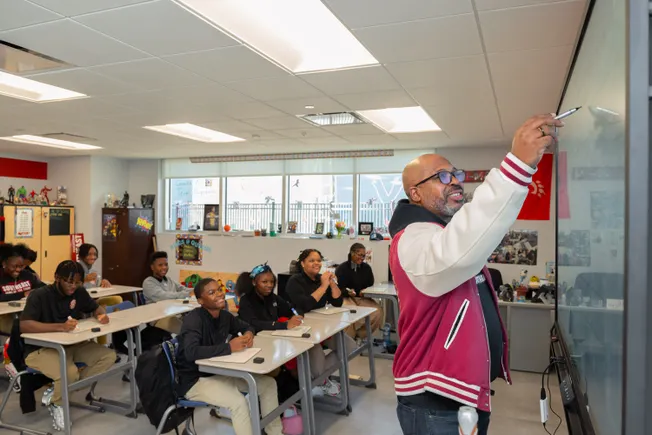

Sean Crowe — a 2nd, 5th and 6th grade math teacher at Congress Heights and math lead teacher for the school — says building intentional, caring and trusting relationships with students and families are vital factors that have helped improve math performance. As a D.C. native, he says he relates to some of the struggles his students are facing, such as family members in the criminal justice system, involved with drugs or other challenges.

But he also credits educators’ high expectations of all students for the school’s math improvements. He tells his students, “During this math class, it’s all about math. Even if you’re having a rough day, we still have to get to work.”

Crowe also says he relies on data analysis of students’ work so he can quickly determine if a student needs extra support, whether that’s 1-to-1 teacher support or skills development using an online platform.

“Anybody in the building will tell you, I am the biggest data hawk besides Ms. White,” Crowe says.

Sean Crowe, a math teacher at Center City Public Charter Schools’ Congress Heights campus in Washington, D.C., reviews a 2nd grader’s work in a school hallway on Jan. 22, 2026.

Kara Arundel/K-12 Dive

Students in a 7th grade classroom work independently to solve math problems at Center City Public Charter Schools’ Congress Heights campus on Jan. 22, 2026, in Washington, D.C.

Kara Arundel/K-12 Dive

Digging into the data

One of the city’s partners that is working to help elevate math performance is EmpowerK12, a Washington-based nonprofit that provides data analytics, tools and training to school systems and is part of the Capital Math Collective.

EmpowerK12 also conducts research into D.C. traditional and charter public schools that are exceeding achievement expectations for “priority students,” including those who are economically disadvantaged, have disabilities, are English learners or are students of color.

There’s no magic formula. There is lots of hard work. The hard work has to be done with consistency and with a team that can handle it.

Niya White

Principal of the Congress Heights campus of Center City Public Charter Schools

In its 2025 report, EmpowerK12 named 16 traditional and public charter schools as Bold Performance Schools for having math and reading proficiency rates at least 10% higher than schools with similar student demographics and grade bands that are at least 30% economically disadvantaged. Center City’s Congress Heights campus was one of those designated a Bold Performance School.

EmpowerK12’s report says leaders of Bold Schools have a “trust but verify” approach, meaning they build strong teaching teams that have autonomy to make instructional decisions and take ownership of student outcomes.

Josh Boots, founder and executive director of EmpowerK12, says the organization’s work includes studying performance data and also researching qualitative information to better understand what factors lead to academic improvements.

“We’re actually — as much as we can — highlighting what are the bright spots for economically disadvantaged students, for students with disabilities, or English learners, or Black and brown kids. What are they doing to solve the problem?” Boots says.

Crystal Powell, then a 1st grade teacher at Friendship Armstrong Elementary School in Washington, D.C., celebrates with students in 2024.

Permission granted by Kea Taylor, Imagine Photography

Being collaborative and flexible

Friendship Chamberlain Elementary School, part of the Friendship Public Charter School network in D.C., was named 2025’s Boldest School by EmpowerK12 for having the highest math and reading proficiency rates above expectations in the city. Three other schools in the network were named as Bold Performance Schools.

Across the Friendship charter school network, 45% of Black students and 42% of economically disadvantaged students scored proficient on the math assessment in 2025. Those performances are 8 and 9 percentage points higher, respectively, than average proficiency rates for Black and economically disadvantaged students attending other schools in the same neighborhoods.

Several initiatives have helped boost math performance across the Friendship network of 15 campuses educating 4,600 students, according to CEO Patricia Brantley.

Those efforts include prioritizing COVID-19 learning recovery by emphasizing core foundational skills during in-person instruction starting in the fall of 2020. The network has also dedicated energy toward teacher development, data analysis and an intensive interest in understanding what factors contribute to high performance.

Friendship Chamberlain Elementary School 3rd grader Nori Anderson embraces math challenges in master teacher William Foster’s class on Nov. 14, 2025, in Washington, D.C.

Permission granted by Kea Taylor, Imagine Photography

One common thread its research has uncovered is a boost from consistent approaches to grade-level instruction and expectations across the network’s schools. That’s because as students move to new schools within the network, they know what’s expected and how their teachers will structure class time, Brantley says.

Some schools in the network practice looping, where teachers stay with a cohort of students as they advance grades. The frequency of this approach depends on teacher interest, but Brantley says it has helped forge closer relationships between teachers and students — and lets teachers better understand students’ learning gaps.

But even with improvements made across the network, challenges remain, Brantley says. For instance, Friendship network’s data shows weaker math and reading progress for 3rd and 4th graders, who were 3 or 4 years old when the pandemic began in 2020 and less likely to be attending preschool then, she says.

Brantley advises school leaders to be critical of the data they see — even as performances increase — and to ensure those positive results aren’t just reflecting the scores of higher performers.

“Figure out who we are not still serving well and support them,” she says. Academic improvement in the city has to be “really meaningful.”