Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When COVID forced schools to close in 2020, everyone — students, teachers, classroom aides and administrators — was forced online together. Everyone scrambled to figure out the technology, everyone hungered for human connection.

Today, with thousands of federal agents targeting Minnesota schools, bus stops, day care centers and other places where immigrant parents gather with their children, remote learning options have been revived in numerous districts, with varying degrees of success. And, unlike the pandemic-era emergency measures, the steps schools are taking to keep kids safe are anything but uniform.

In many schools — especially those that enroll diverse student bodies — who can show up and who can’t changes by the day, forcing teachers to improvise continually. Still confronted with the absenteeism, mental health crises and lost learning of the pandemic shutdowns, educators know what’s being lost — and exactly which children are going to suffer the disproportionate impact of an emergency now in its ninth week.

Two St. Paul Public Schools teachers recently gave The 74 glimpses inside their classrooms. In his 18th year on the job, John Horton teaches at Barack and Michelle Obama Montessori, where classes contain multiple grade levels and the student body, as he puts it, “looks like the people that live in St. Paul.” So far, all 28 of his first, second and third graders have been in school, every day.

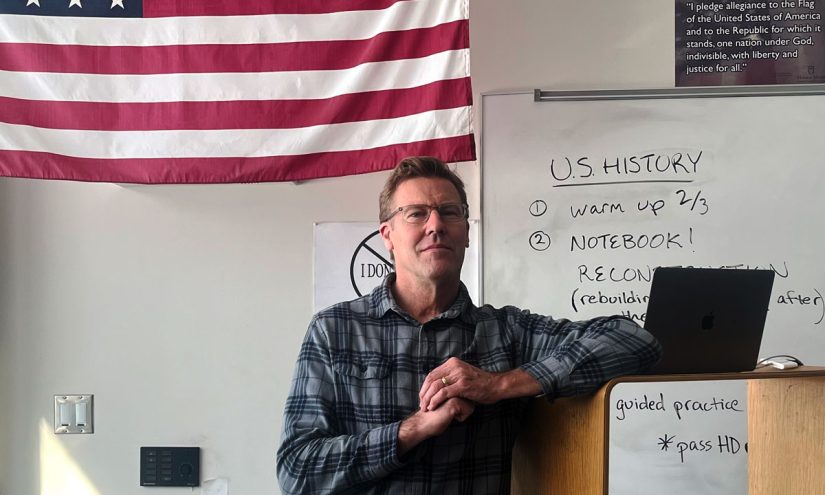

Across the city, in the equally diverse Como High School, 31-year veteran Eric Erickson teaches a host of subjects where current events are inescapably relevant: AP Psychology; a University of Minnesota College in the Schools government course; and U.S. history, co-taught with an English learner instructor.

As ICE Targets Twin Cities Schools & Bus Stops, Even Citizens Keep Kids Home

As improbable as it sounds, the families of Horton’s pupils want them physically present in class and have moved mountains to get them there safely. But the divides in in-person attendance in Erickson’s classes are illustrative of a deepening inequity. He knows that a persistent chasm of unequal opportunity is likely to yawn wider.

Until the abduction of a child or violence at or near their school forces them into the spotlight, most Minnesota educators have been too fearful to speak out, using their names and those of their schools, about what it’s like in classrooms right now. Yet Horton and Erickson, both of whom have been Minnesota Teacher of the Year finalists and/or semifinalists, told The 74 they want people to know what school is like in this unprecedented moment.

These excerpts from conversations with them have been edited for length and clarity.

Who’s in class in person, and who isn’t

Horton: Children really, really thrive on structure, routine, predictability. The problem that’s different from COVID to now is that during COVID, even though things were upended, there were still some structures and routines and things in place. But with the way things are heading right now, those things aren’t present anymore.

Barack and Michelle Obama Montessori teacher John Horton. (Courtesy of John Horton)

Our school has some teachers that have been reassigned to take on virtual learning. They’re pausing their in-person job and moving to the online school. They’re teaching children who haven’t ever been to online school. So it’s a whole new program and a whole new mode of instruction.

My classroom has 28 kids normally, and I have 28 kids still here. I have a very good relationship with a lot of the families, and they really wanted to stay in person as a community. There’s definitely some fears and anxiety, but for young children, that predictability is really important.

We are fortunate to have a community of volunteers keeping watch around the school. We have precautions in place for children who don’t feel safe waiting for the bus. There’s been a lot of community- and school-level action that has helped mitigate the fear. But there’s a lot of anxiety about leaving the house.

Erickson: The students who are not here tend to be students with brown skin and black skin. And in many ways, this division along race and ethnicity makes this version of virtual learning feel a lot more like battles we thought we had overcome in the Civil Rights Movement, and with equal access to opportunity and education.

The difference in who’s here and who’s not can be seen in the difference between a U.S. history English-language cohort and a senior-level, University of Minnesota college-level government course. I’ve got 95% of my seniors in college-level government present, and about 30% of my co-taught U.S. history classes are online. But our English-learner classes, some of them are less than half in attendance in person.

Amid Fed Ramp-up and New Fears, Twin Cities Schools Offer Online Classes

(Students are) not able to listen to their (in-person) peers and process what’s happening. They’re living in isolation with their family and social media as connectors, as opposed to the support of peer-to-peer and caring adult interaction.

We are still their teachers. They are still on our class lists. We are pushing out lessons, videos, documents and assignments to students in their homes. But there’s no substitute. Students who miss live instruction and interaction with peers and their teachers cannot obtain the same quality of education.

What they’re hearing from students

Horton: The challenges the kids are experiencing at home and in the community are real. Children talk openly about the immigration crackdown. They’re making posters and expressing their frustration. A couple of my kids have been to protests. A few of my kids have had knocks at the door and agents enter their homes.

And, of course, a lot of children are aware of what’s going around the community because of parents’ stress. In a lot of ways that’s very similar to COVID, where families are trying to isolate children from everything that’s going on and yet the children know something is going on.

I don’t know if I can share all my stories. There was an incident at a child’s house a couple weeks ago. And that was scary. The child was scared, the family was scared. I was shook. They called me Sunday at 6:50 in the morning to tell me what was going on. Some of the people in our community are going through a lot, and they don’t have a lot of people they might be able to know or connect with or trust.

I’ve worked with these families for three years in a row, and I have good relationships. There’s a lot of blessings with that and also heartbreak. It’s really hard to hear what’s transpiring, but I’m also really surprised by the outpouring of love.

When they’re struggling through traumatic events — and our city has been through so many over the last few years — children also need a sense of hope and joy. To see their friends, to have things they know how to do, be it an art project or something. Having those things, those distractions, those avenues are really important. The children that have been coming to school have been very happy in my class.

Erickson: When we are debriefing the current events in the news cycle, Minneapolis and St. Paul are at the center of a federal surge that has drawn the attention of the world. It’s imperative that we’re able to discuss, analyze and evaluate the impact of the situation surrounding us. I take pride in listening to my students, taking their questions and helping them think critically about what we’re experiencing in relationship to what we’ve studied with the Constitution, separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism.

They ask appropriate questions. They see injustice. They observe an overreach of federal power. They notice that the guardrails are off with regard to checks and balances. Congress is not holding the Executive Branch accountable. Court decisions are not necessarily checking the expansion of presidential power. They wonder if it’s their time and place to exercise their First Amendment rights.

How students are expressing themselves

Horton: This is a Montessori school, and we believe in honoring children’s voices. The posters children have written are very simple. They say “ICE out.” Or, “Leave our friends alone.” “You are not welcome” is one of my favorite ones. The kids are expressing themselves through art. Having that outlet is so important.

The kids started a food shelf in the classroom. And they’re collecting money for the International Institute of Minnesota [a St. Paul nonprofit that helps refugees and immigrants resettle]. Two children are carrying around a box, collecting change.

Families have donated gift cards to support other families. To see all the people coming together, that makes me hopeful.

Erickson: We saw a highly organized, peaceful student protest on Jan. 14, a week after Renee Good’s killing, where students from across St Paul high schools — mostly public, but also peers from private and charter schools — converged on the state Capitol to call out the injustices they’re seeing and to ask for human decency from the federal government.

We were fearful as a school community about what might happen to them if they exercise their freedom of speech and freedom to assemble. We were inspired to see them advocate for themselves. We, of course, did not attend or endorse the student walkouts. But parents and community members coordinated to serve as unofficial marshals and watch over the routes they were taking to the Capitol, and to be there for support, to be observers of their constitutional rights.

Minneapolis Schools Shut Down for 2 Days in Wake of ICE Clashes, Fatal Shooting

There were three students in the room with me, the other 20 were at the rally. We were able to watch a livestream. And as we observed democracy in action, two of their classmates gave speeches on the steps of the Capitol. One addressing the humanity of all people and immigrants being the backbone of this country, and another addressing the impact of ICE’s actions. They were articulate messages — positive and hopeful in tone — while also criticizing the overreach of the federal government.

Their own mental health

Horton: Well. Oh boy. That’s a doozy of a question. My job is to make sure the children are safe and secure, and sometimes that means that you have to co-regulate with them. You have to show them what calm, caring and compassion looks like. And also anxiety. You need to model it: “I’m feeling this way, and this is how I can deal with it.” It’s almost like you’re teaching as you’re feeling, which is tough.

And then my own children. You know, what they hear when I talk at home. I’m trying to be a really good role model, and that comes first. Sometimes as an adult and a parent and someone in the community, you just have to put aside your own preferences for the good of the group.

Talking to children about hard things is important, but they can only take so much at a time. As a teacher, and especially a teacher of young kids, having difficult conversations is part of life. But they really need time to process things. Talking briefly about these incidents and then giving them an opportunity to have a say and have some hope and have some joy in their life is very important.

The hardest thing for me is I know the impact it’s having on our families. That’s really hard. And I also know it’s impacting staff. There’s staff that carry around documents now, and they’re scared to go out.

Mothers of Major Resistance: PTA Members Organize Minneapolis Relief Efforts

I keep using the word “community,” but I really have found a lot of comfort in that. You know, comfort with the children, the families, the staff. But to say it’s easy would be a lie.

It’s a relief in some ways that they can be together. Just being in community is such a powerful thing for the people out protesting — even in our classroom.

Erickson: As much as I pride myself on teaching from a non-partisan perspective and analyzing political issues and the role of government with objectivity, seeing the harm to our students and families has caused me to choke up more than once in class while listening and guiding discussion on these matters.

Yes, it has taken an emotional toll on teachers. Teachers love and care for all of our students. To have 30% of them not be able to reach school and go to your class where they belong is a cruel and sad injustice.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how